Political Parties

Role and goals of parties

- A political party is an autonomous group of citizens having the purpose of making nominations and contesting elections in the hope of gaining control over governmental power through the capture of public offices and the organisation of government. (Huckshorn, as cited in Katz 2017: “Political Parties”, p. 214).

- A Party is a body of men united for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed (Burke, as cited in Katz 2017: “Political Parties”, p. 215).

Roles of parties

From Séance 7-Institutions of Comparative Democracies II.

- E.E. Schattschneider: “The political parties created democracy and modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.” (E. E. Schattschneider, Party Government, New York, 1942, p. 53.)

- The actor who organises the fusion of powers are parties.

- The actor who makes separation of powers at all workable is parties.

- Parties promise to support an individual, a policy… Voting for an individual without a party behind them would make it difficult to predict who’s gonna be prime minister. Parties organise this.

- If parliament was just a loose set of MPs how would they negotiate between them? Parties push their MPs to accept certain compromises and set common ideology.

More specifically

- Representation of interests: Being the voice of different interests; reacting to changes in the preferences of the electorate.

- Organisation of interests: Distill policy programs from the diffuse interests of their voters.

- Mobilisation: Communicate politics to voters. Conduct electoral campaigns and structure competition.

- They politise→turn apathy of voter into interest (engagement).

- Governing: Recruit and socialise potential officeholders, coordinate relationship between parliament and government, be accountable.

- Training young ones, etc…

Goals of parties

- Policy seeking: Implement the program of the party

- Vote seeking: Maximising the share of seats in parliament

- Office seeking: Becoming member of government

- These goals can be in conflict with each other!

- When you are an opposition party you seek office, but you can’t seek policy f.ex.

- And what if policy goals aren’t aligned with majority of voters?

- If your policy seeking annoys other parties you wont be able to seek office.

Type of parties

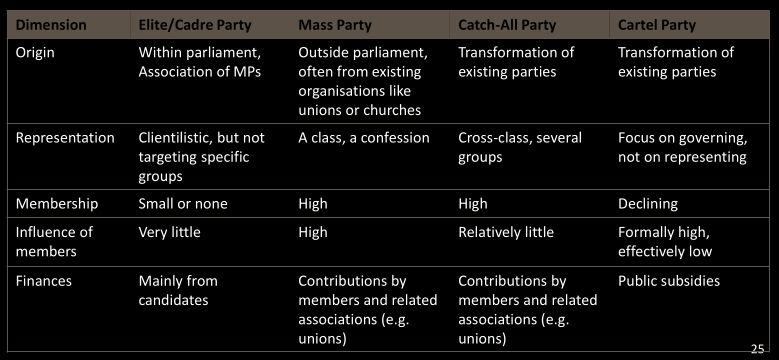

Elite parties

- Example: Liberal and Conservative parties in the 19th century

- Originates in parliament as association of MPs (⇒ 19th century, MAJ voting).

- Loose organisation, clientelistic rather than programmatic appeals.

- No or little membership.

Mass parties

- Example: Socialist, Communist, Fascist Parties.

- Originates outside of parliament.

- Strong organisation, programmatic appeals.

- Mass membership, strong influence of members.

Catch-all parties

- Example: Christian Democrats, Social Democrats and Conservatives after World War II.

- Transformation of existing parties (Christian Democrats partly an exception).

- Strong organisation, competence appeals.

- Mass membership but relatively little influence of members.

Catch-all parties and the median voter theorem

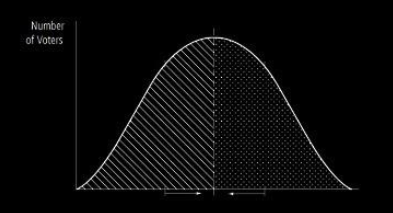

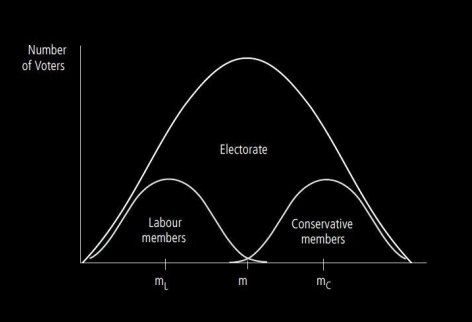

- The median voter theorem (Downs, A.: An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York 1957): In a two-party system, parties will converge on the median position on the main axis of competition.

- Parties will thus become (almost) indistinguishable programmatically.

- Radicals wont change their vote so it’s only beneficial to tone down positions on anti-capitalism or anti-immigration, etc… Become tolerant basically.

The cartel party thesis

- Most importantly, looking at these three models as a dynamic rather than as three isolated snapshots, suggests the possibility that the movement of parties from civil society towards the state could continue to such an extent that parties become part of the state apparatus itself. It is our contention that this is precisely the direction in which the political parties in modern democracies have been heading over the past two decades.

- Less and less integrated with civil society and closer leaning to the state integration.

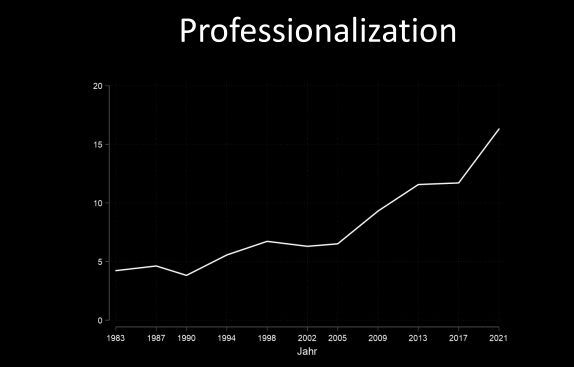

Member of parties are still people that’d work in fields relative to their position (those in worker movements would be workers→craftmans etc… f.ex.). Nowadays they are very professionalised, they work in politics.

Member of parties are still people that’d work in fields relative to their position (those in worker movements would be workers→craftmans etc… f.ex.). Nowadays they are very professionalised, they work in politics.

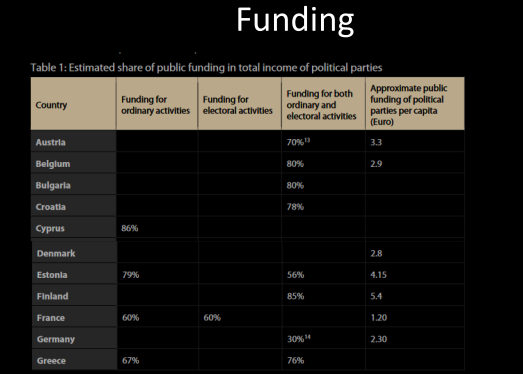

Mostly funded by the state in many countries (50%+ from taxpayers). Thus:

Hence we see the emergence of a new type of party, the cartel party, characterised by the interpenetration of party and state, and also by a pattern of inter-party collusion. In this sense, it is perhaps more accurate to speak of the emergence of cartel parties, since this development depends on collusion and cooperation between ostensible competitors, and on agreements which, of necessity, require the consent and cooperation of all, or almost all, relevant participants.

Mostly funded by the state in many countries (50%+ from taxpayers). Thus:

Hence we see the emergence of a new type of party, the cartel party, characterised by the interpenetration of party and state, and also by a pattern of inter-party collusion. In this sense, it is perhaps more accurate to speak of the emergence of cartel parties, since this development depends on collusion and cooperation between ostensible competitors, and on agreements which, of necessity, require the consent and cooperation of all, or almost all, relevant participants. - Together they have become a cartel that controls how politics is conducted→keeping outsiders out f.ex.

- This is contested, no party would be proud to be a part of this.

- This type is more controversial! Parties would proudly describe themselves as “Mass” or “catch all” but not as “cartel”!

- Example: Christian Democrats, Social Democrats, Liberals after 1990.

- Transformation of existing parties.

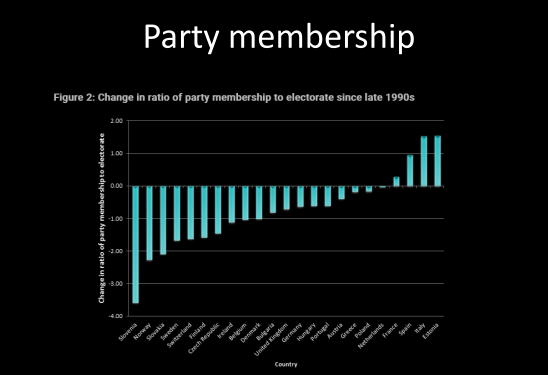

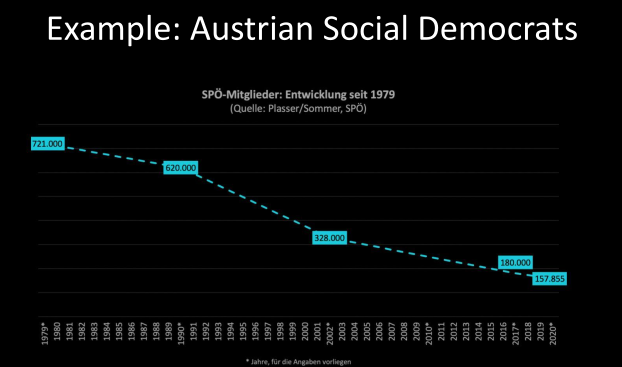

- Leadership increasingly independent, competence appeals, professionalization.

- Small membership, little influence of members.

- Increasing symbiosis of parties and state.

- Not an objective text but wants to put forward a controversial argument and hear counterarguments, tries to state this has already happened.

- No alternatives, parties say they understand and are professional. It’s not that much about ideas but about being knowledgeable.

Summary

Internal organisation of parties

- Robert Michels, 1911: The “iron law of oligarchy”: “It is organisation which gives dominion of the elected over the electors. […] Who says organisation, says oligarchy.”

- As movements become bigger, they need to organise and develop bureaucracy. Otherwise, they will dissolve (e.g. Occupy Wall Street).

- The interests of professional party organizers are necessarily different from those of members.

- Like longevity (if the organisation dissolves so does your job)→cartel structure guarantees it.

- Gaining office and not being able to pursue everything is also an example here.

- There is necessarily an asymmetry in information between party professionals and members.

Challenging the iron law: Movement parties

Often, new parties explicitly seek to challenge the iron law of oligarchy. Two strategies: Weakening the professionals and/or strengthening the members.

- Green parties in the 1980s: Rotation of MPs, incompatibility of party office and parliamentary mandate, dual leadership…

- Pirate parties: “Liquid Democracy”.

- The Movimento 5 Stelle: Attempt to organize party, have internal discussions and votes through online platform “Rousseau”. ⇒ Rather seems to demonstrate that Michels’ law is indeed quite powerful.

Challenging the iron law: Primaries

Nomination of candidates for parliament/government usually through party sections and party congresses. Alternative: primaries. Established in the US, increasingly common in other countries.

- Open (everyone) vs closed (members only).

- Combination of party pre-selection and membership votes (UK).

- French Republicans used open primaries in 2017, more than 4 million people participated, no primaries in 2022.

Primaries and the median voter theorem

- The median voter theorem: To win a majority, a party (or coalition) needs to win the vote of the voter who has in the middle of the ideological distribution. This will induce a moderation of right and left parties (Downs 1957, see below).

- Problem: To win a primary, a candidate needs to win a majority of primary voters (often party purists).

- This makes it very difficult for moderate candidates and favours the selection of purists.

This hurts the party as it deprioritises the office seeking objective, as such party elites nominating someone will eventually happen.

This hurts the party as it deprioritises the office seeking objective, as such party elites nominating someone will eventually happen.

Challenge or evidence for the cartel party thesis?

The distinction between members and nonmembers may become blurred, with parties inviting all supporters, …, to participate in party activities and decisions. Even more importantly, when members do exercise their rights, they are more likely to do so as individuals rather than through delegates, a practice which is most easily typified in the selection of candidates and leaders by postal ballot rather than by selection meetings or party congresses. This atomistic conception of party membership is … obviating the need for local organizations, and hence also for local organizers.

Party systems

- Definition: In its simplest form, the party system is conceived of as a set of patterned relationships between political parties competing for power in a given political system.

- Not separated, parties react to each other. They compete for certain voters for which they don’t have a stronghold.

Types of party systems

- The simplest distinction: two-party-systems vs multiparty systems.

- Two-party systems: One party governs, the other party is in opposition, competition for the median voter.

- Multiparty systems: Coalition government, thus, relationship between parties much more diverse.

- A “bipolar” system is a multiparty system in which two stable blocks of parties compete for power. E.g. Sweden during postwar decades.

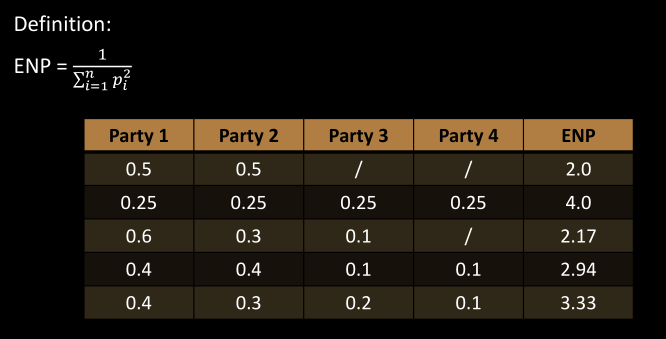

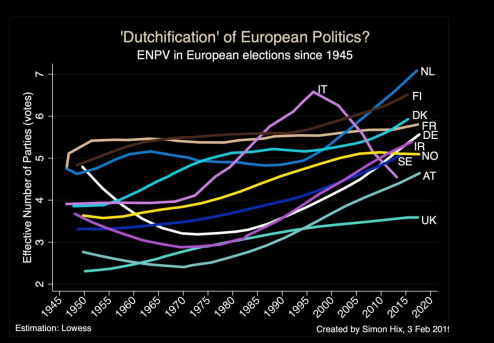

The effective number of parties

Increasing fragmentation

An institutional explanation for party systems

“Duverger’s” law: → see session 6: MAJ systems tend to have two party systems.

- Modification: several regional two-party systems in the same country (Canada: Bloc Québécois, UK: SNP).

- Two mechanisms behind this “law”:

- Mechanical effect: below a certain threshold, parties win few or no seats.

- Psychological effect: voters don’t want to waste their votes.

Problem

The institutionalist explanation makes a strong prediction for MAJ systems but makes no predictions for PR systems (but: role of electoral thresholds). In particular, it does not explain which parties emerge.

- E.g. Why does England have a different 2.5-party system than Scotland?

- E.g.: Why did the British two-party-system change from Conservative- Liberal to Conservative-Labor?

- E.g. Why do Germany and Switzerland have strong Green parties but Italy and Spain do not?