From Forest to Air Pollutant

Incentives

- The use of incentives may be the best way of capturing forest externalities.

- Forest certification schemes, e.g. Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

- Payments for Environmental Services (PES), e.g. Pagos por Servicios Ambientales, in Costa Rica.

Bargaining solutions

- Norway gives Liberia up to a hundred and fifty million dollars in aid, in exchange for which Liberia will work to stop the rapid destruction of its trees.

- Similar approach with Brazil.

- Payments for ecosystem services.

- Coase theorem (1960) bargaining between parties could, under certain conditions, produce a mutually beneficial and efficient solution.

- Socially suboptimal situations (e.g., too little provision of environmental services) can be resolved through voluntary market-like transactions.

- High transaction costs when many actors (countries f.ex.) involved.

Payments for ecosystem services (PES)

- PES are a voluntary transaction between at least one buyer and at least one seller in which payments are conditional on maintaining an ecosystem use that provides well-defined environmental services

- The payments thus provide a direct, tangible incentive to conserve the ecosystem and prevent encroachment by others.

- REDD (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) policies have been a centerpiece of international climate change negotiations (Stern 2008, International Union for Conservation of Nature 2009, United Nations 2009).

- Future financial flows for REDD, mainly from developed to developing countries, are predicted to be close to US $30 billion a year (United Nations REDD Programme).

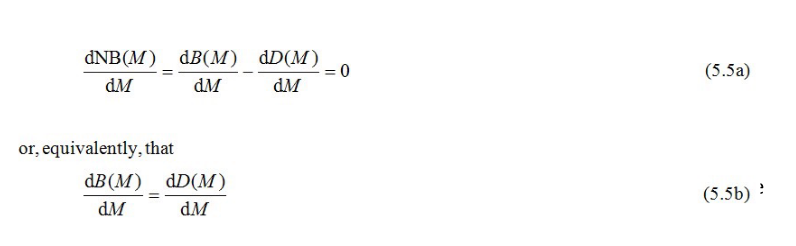

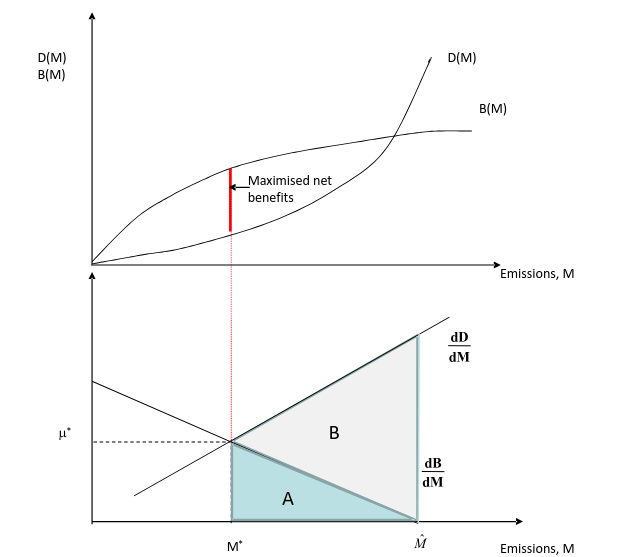

Efficient level emissions or deforestation

- The level of deforestation at which net benefits are maximised is equivalent to the outcome that would prevail if the pollution externality were fully internalised.

- Damage (D) is dependent only on the magnitude of the deforestation (M): D = D(M).

- We assume:

- B = B(M).

- Define:

- NB = B(M) – D(M).

Maximisation of net benefits : emission efficiency condition

To maximise the net benefits of economic activity, we require that the

deforestation, M, be chosen so that :

Total and marginal damage and benefit functions, and the efficient level of flow emissions/deforestation.

Total and marginal damage and benefit functions, and the efficient level of flow emissions/deforestation.

Conditional cash transfers to landowners who maintain forest clover

- These PES programs are designed to increase the private returns to forest and thus reduce the difference between private and social values of forest.

- PES programs can provide a steady stream of income in poor areas.

- An attractive win-win policy solution.

- Mexico, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Brazil have already established payments for avoided deforestation programs while other countries are experimenting with them (Jindal, Swallow, and Kerr 2008, Wunder and Wertz-Kanounnikoff 2009, United Nations REDD Programme 2011).

Issues with PES

- Additionality, leakage.

- Pattanayak et al. 2010: Results are highly divergent.

- Besides, well-defined land or resource-tenure regimes for providers.

- PES do require a payment culture and good organisation from service users.

- A trustful negotiation climate (Wunder, 2013).

- See Borner et al. 2017 for a survey.

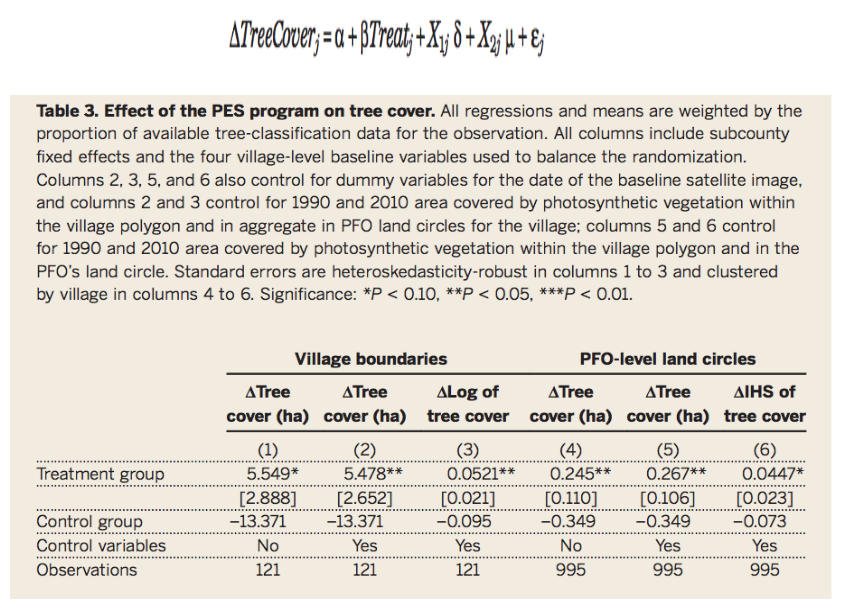

Jayachandran et al. 2017: Uganda program for forest-owning households

- Annual payments of 70,000 Ugandan shillings per hectare if they conserved their forest.

- The program was implemented as a randomized controlled trial in 121 villages, 60 of which received the program for 2 years.

- To be sure there is causation and not only correlation we need to keep every other value the same.

- The primary outcome was the change in land area covered by trees, measured by classifying high-resolution satellite imagery.

- Tree cover declined by 4.2% during the study period in treatment villages, compared to 9.1% in control villages.

- No evidence of leakage.

- No enrollees shifted their deforestation to nearby land.

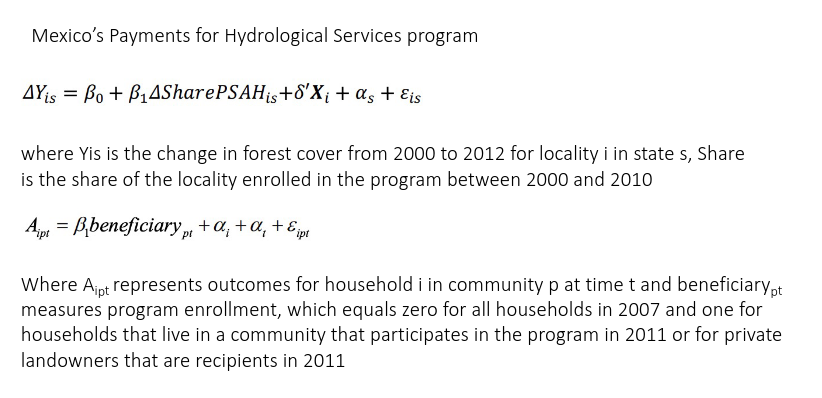

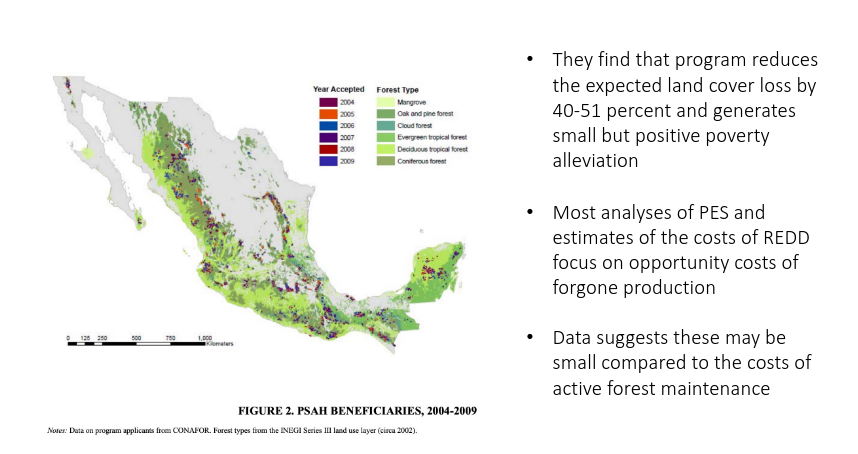

Alix-Garcia and Sims 2015

Unconditional Payment can be counterproductive

- Wilebore et al. 2019.

- Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of unconditional livelihood payments to local communities on land use outside a protected area –the Gola Forest, a biodiversity hotspot on the border of Sierra Leone and Liberia.

- Detailed satellite imagery data from before and after the intervention was used to determine land use change in treated and control villages.

- Negative effect of unconditional payments on land clearance (4% additional land clearance in treated villages).

In Summary

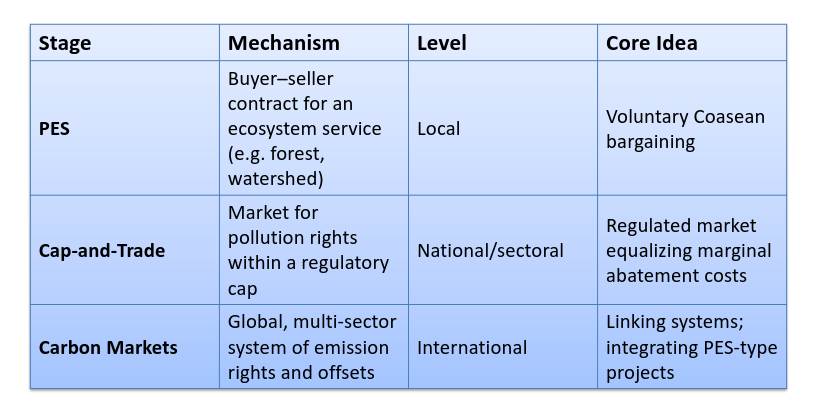

- Voluntary, conditional payment from buyers to providers of ecosystem services.

- Coasean Logic: Direct contract between provider and beneficiary.

- Costa Rica PSA: forest conservation payments;

- Norway–Liberia deal: aid for avoided deforestation.

- Mexico hydrological services (Alix-Garcia & Sims 2015): 40–50% reduction in cover loss.

- Uganda RCT (Jayachandran et al. 2017, Science): +5% forest retention, no leakage.

- Gola Forest (Wilebore et al. 2019): unconditional transfers increased clearing.

Success Factors

- Conditionality (payment linked to verified outcome).

- Additionality (change vs. baseline).

- Leakage control.

- Secure tenure (property rights prerequisite).

- Takeaway: PES works when rights are clear and contracts enforceable.

- PES shows us how we can pay landowners directly to conserve forests.

- But how do we scale this idea up when millions of emitters are involved?

- We fix the total quantity of emissions and let firms trade allowances — that’s cap-and-trade.

- And when we link these systems globally through carbon credits and REDD+, we arrive at carbon markets.

- Cap-and-Trade shows how government formalizes this principle at scale — turning a bilateral bargain into a full market with a cap.

Cap and Trade

- Cap-and-trade (also called tradable emissions allowances) sets a firm cap on total emissions from regulated sources and then allocates or auctions allowances that sum to this cap. Each allowance authorizes its holder to emit a specified quantity (e.g., one ton of SO₂ or CO₂)..

- Allowances can be bought, sold, or banked, creating a market that equalizes marginal abatement costs (MACs) across emitters — the condition for cost-effectiveness.

Carbon Markets: Globalising the PES logic

- Carbon Markets: Globalizing the PES Logic

- Carbon Markets: Apply the same PES principle globally—buyers pay for verified emission reductions.

- Both internalise externalities by creating a price for carbon storage or emission avoidance.

Cap-and-Trade Systems:

- National or regional caps (EU ETS, RGGI, California ETS).

- Firms trade allowances → equalise marginal abatement costs.

- Offset Mechanisms (Baseline-and-Credit):

- PES-type projects that generate tradable carbon credits (REDD+, afforestation, soil carbon).

- Credits sold to entities that exceed their caps or pursue voluntary neutrality.

Still Coase

- Define rights, measure outcomes, allow trade.

- Carbon markets institutionalise Coase’s logic at planetary scale — replacing bilateral bargaining with a global marketplace for verified carbon outcomes.

Design & Integrity challenges

- Additionality: Are reductions beyond business-as-usual?

- Leakage: Does activity shift emissions elsewhere?

- Permanence: Are forests and soils stable carbon stocks?

- Measurement (MRV): Monitoring, reporting, verification.

- Equity: Who benefits from credit revenues?

In summary

Evolution and Issues with Carbon Markets

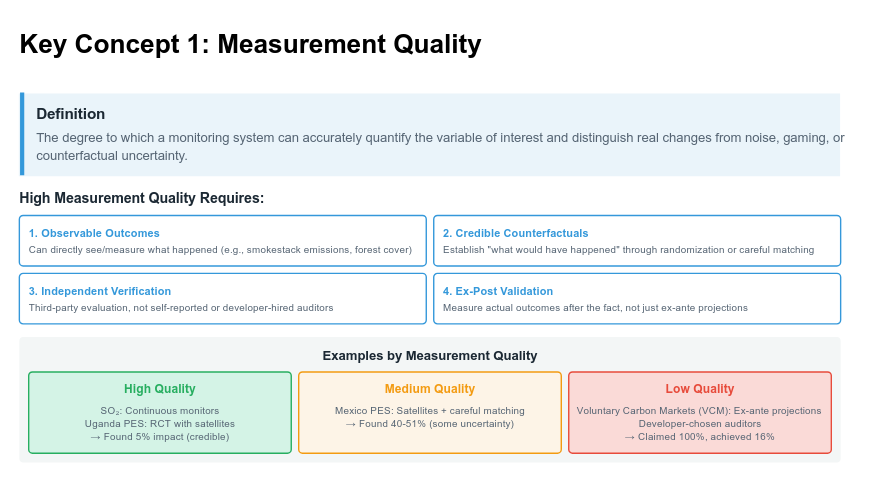

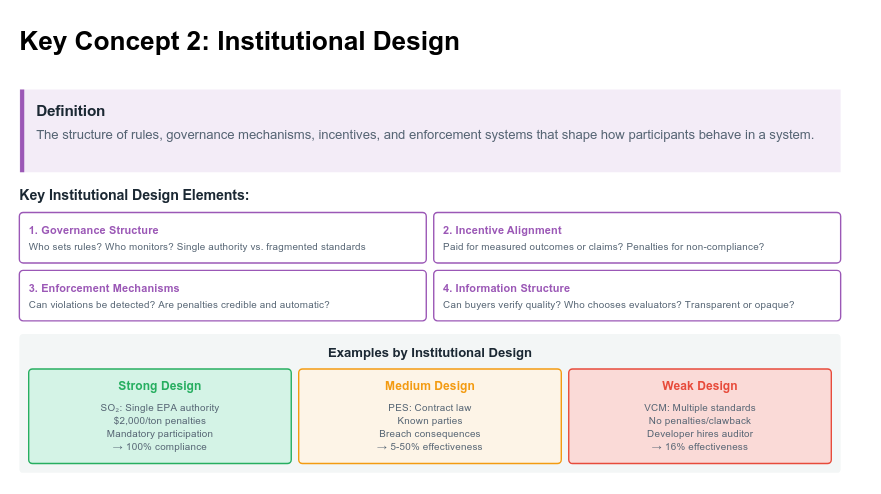

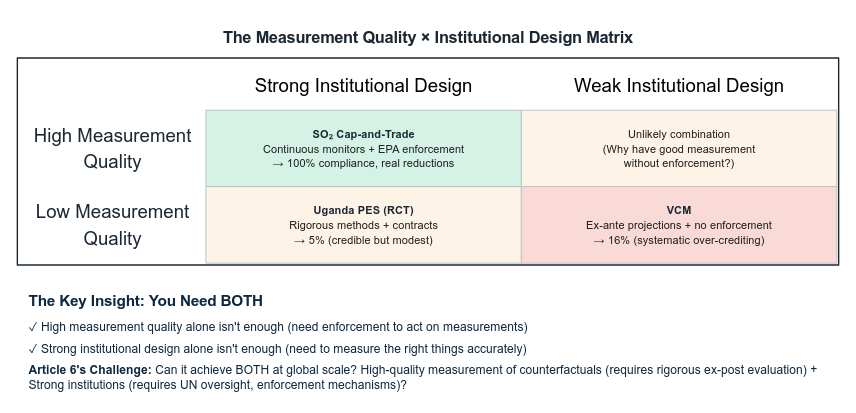

Measurement Quality

Institutional Design

How They Work Together

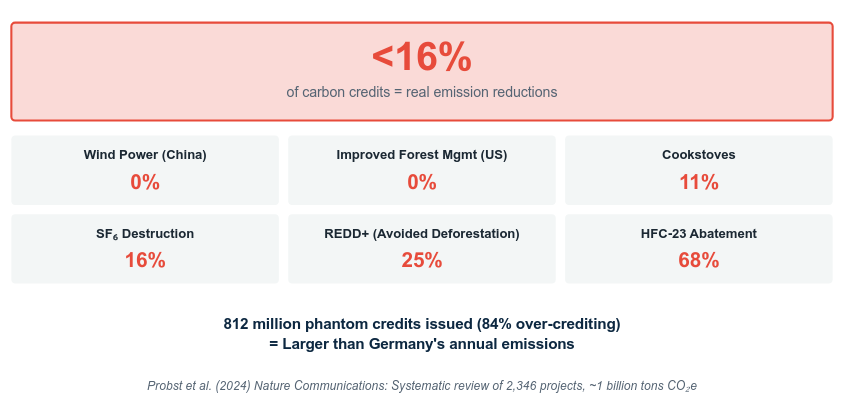

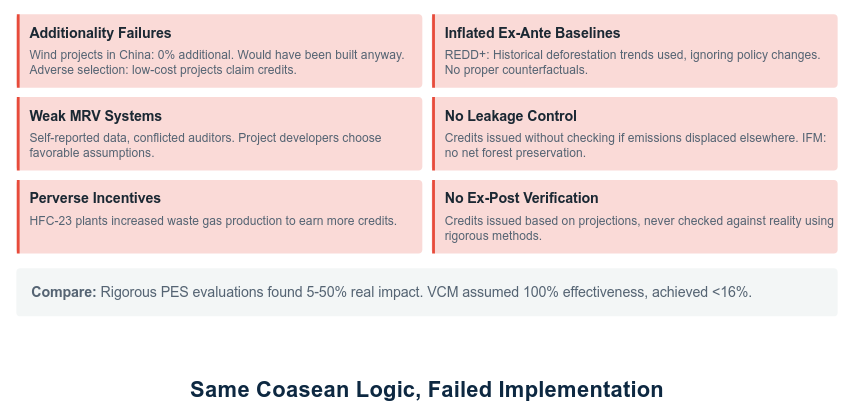

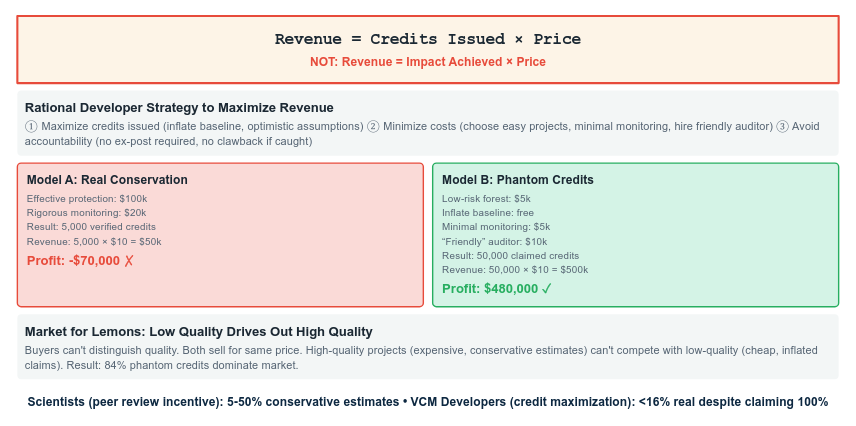

The Issue with Voluntary Carbon Market

What happened? Did VCM fail then?

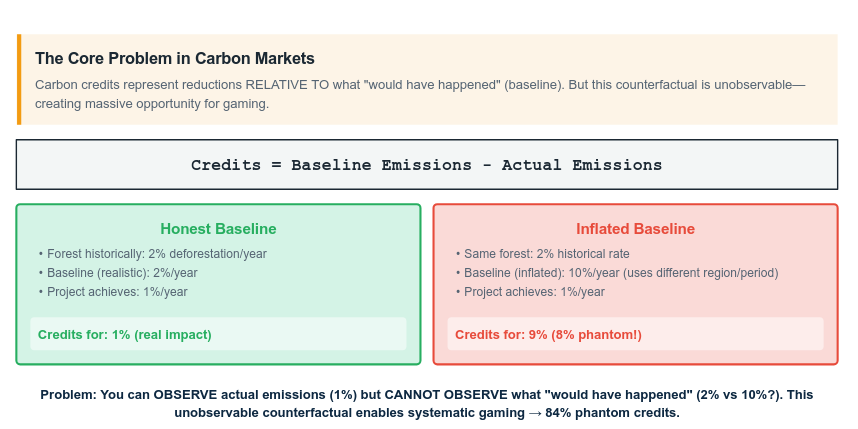

The Inflated Baseline Problem

Real examples: how baselines get inflated

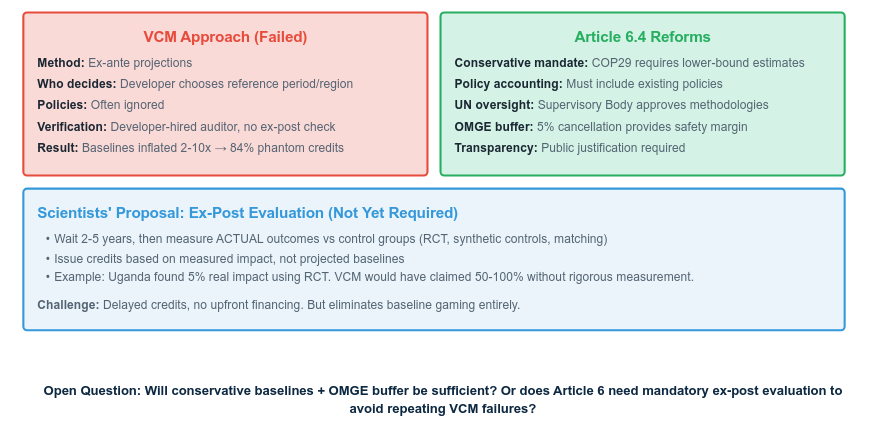

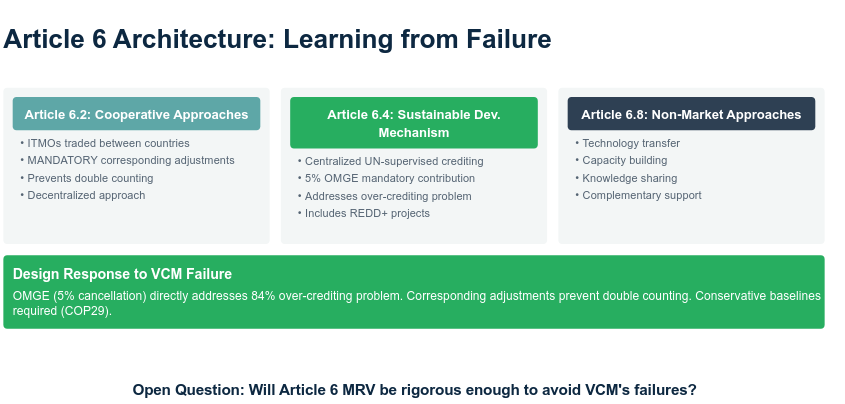

How article 6 adresses it

The self-selection paradox

The Incentive Problem

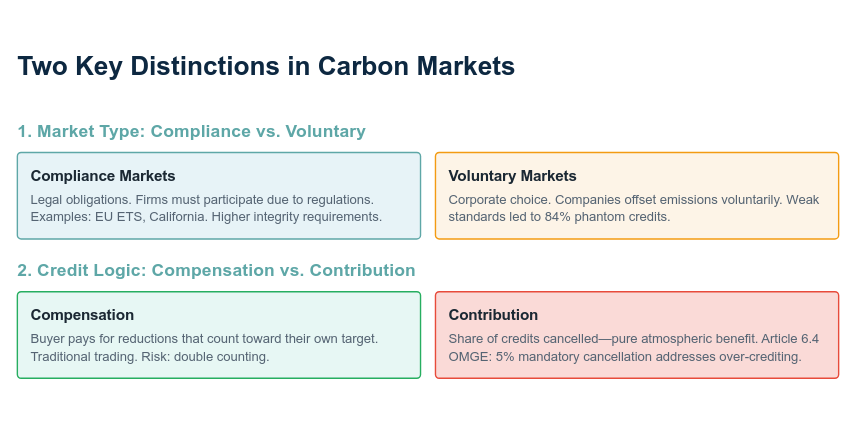

Key distinctions in Carbon Markets

Learning from Failure

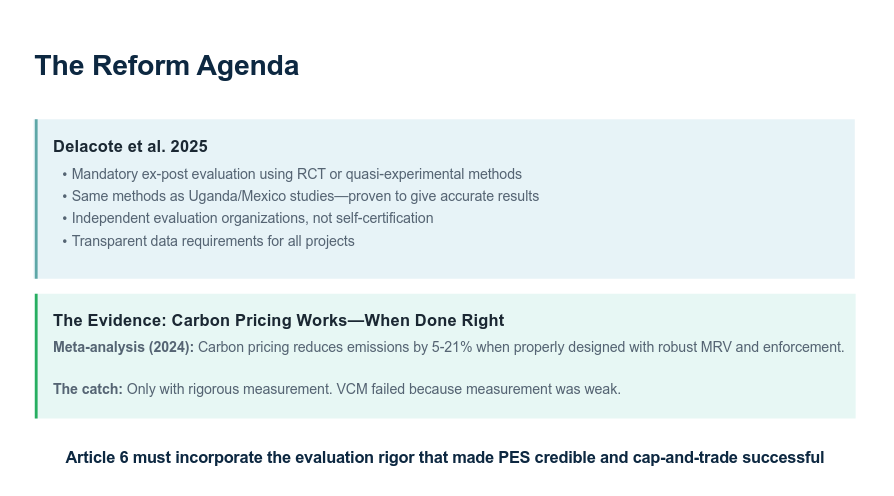

Reform Agenda

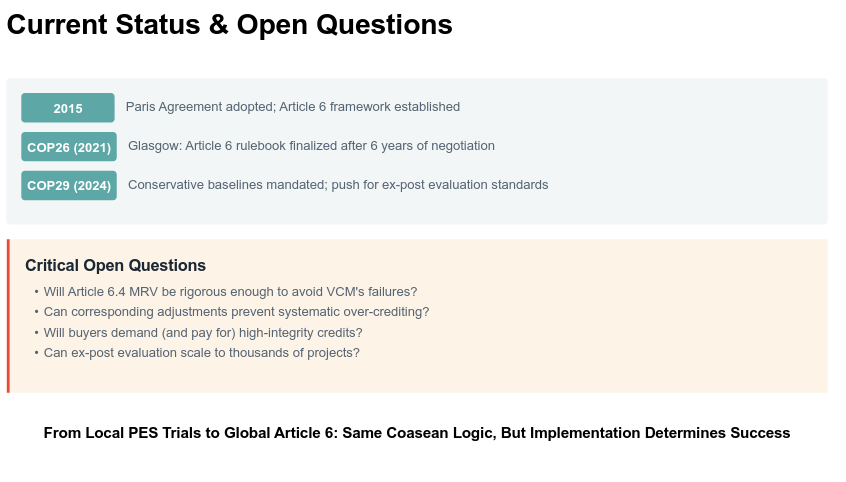

Current Status & Open Questions