Climate change economics

Weather and Climate Change

What is the difference between Weather and Climate?

- Weather is a specific event—like a rainstorm or hot day—that happens over a few hours, days or weeks.

- Climate is the average weather conditions in a place over 30 years or more.

What is Climate Change?

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g. using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties, and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. It refers to any change in climate over time, whether due to natural variability or as a result of human activity.

Why Climate Change

- Why do we talk about climate change in a course titled introduction to Environmental Economics?

- Ongoing and future patterns of climatic change may hinder future growth and development.

Climate change as an economic problem

- There exist a number of reasons that make climate change such a big economic problem:

- It is an absolutely global crisis, which affect every part of the planet as every part of the world is contributing to the problem.

- The problem crosses not only countries but also generations:

- The people who are going to be most profoundly affected by human-induced climate change have not yet been born, and there is no one representing their interests.

- The problem of GHG emissions goes to the core of modern economy:

- What is needed is a kind of heart transplant, replacing the beating heart of fossil fuel energy with an alternative based on low-carbon energy!

- Climate change is a slow moving crisis:

- It is actually a very-fast moving crisis from the perspective of geological epochs, but very slow from the point of view of daily events and the political calendar.

- The solutions to climate change are inherently complex:

- The kind of changes that are needed involve every sector of the economy, including buildings, transportation, food production, power generation, urban design, and industrial process.

The consequences of human-induced climate change

- Life on hearth is possible because certain gases (e.g. CO2) trap sunlight in our atmosphere and keep us warm.

- But in excess, these gases may work against us, holding in too much heat, blocking outward radiation, and altering our climate.

- Such changes could affect agricultural yields, timber harvest, and water resource productivity.

- Rise in the sea level, ocean acidification, more storm and floods, etc.

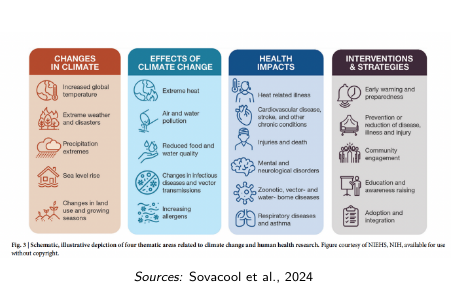

- Human health could be threatened by more heat waves and spreading tropical diseases.

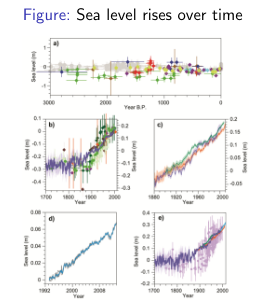

- The average sea level has increased roughly 1/4 of a meter since the late 19th century, causing more storm surges and coastal erosions:

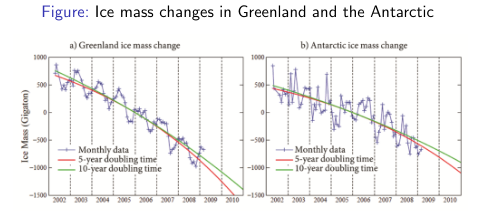

- Human impact is causing a massive loss of these ice-sheets and a massive rise in the sea level, which will likely have dire consequences for the urban areas hugging the oceans and for the food supply around the world:

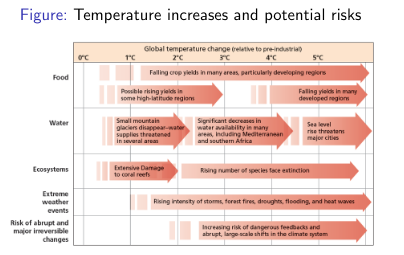

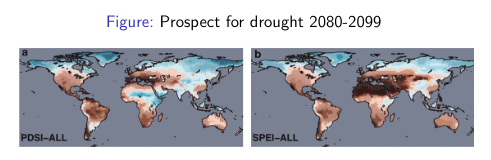

- The consequences of a business as usual (BAU) trajectory for this planet could be absolutely dire:

- The temperature increase by the end of the century could be as much as 4-7◦C, which would have devastating effects.

- The temperature increase by the end of the century could be as much as 4-7◦C, which would have devastating effects.

- What would happen at a 4◦C increase?

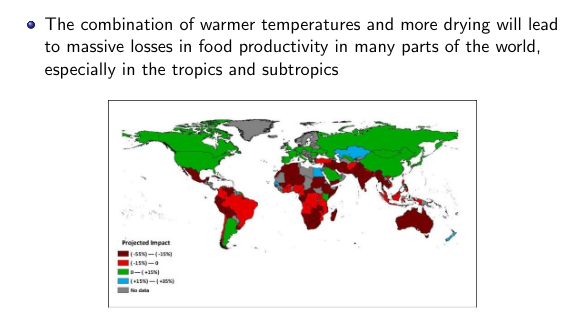

- Entire regions of the world would experience major declines in crop yields, with up to a 50% decline of crop yields in Africa, which would result in massive hunger.

- If temperature rise by more than 4◦C, the consequences are absolutely terrifying.

- Glaciers would disappear, soil moisture will be lost, rainfall will decline in many regions, and extreme events such as massive heat waves, droughts, floods and extreme tropical cyclones will all become more frequent.

- The ensuing sea level rise would threaten major world cities, including London, Shanghai, New York, Tokyo and Hong Kong.

- It is worth noting that these are scenarios, and not predictions.

- Scenarios are not-implausible, internally consistent storylines of how the future might unfold.

- Scenarios can be defined as conditional predictions, and so based on assumptions about population, economy, technology and mitigation policies.

GHGs emission in the atmosphere

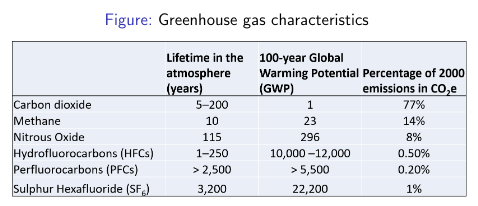

- The total warming effect of all anthropogenic GHGs is determined by adding up the separate radiative forcing of six main GHGs, which account for about 99% of the total greenhouse effect.

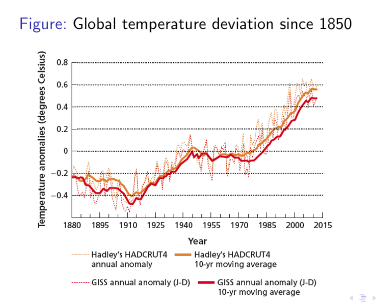

Rise in temperature since the Industrial Revolution

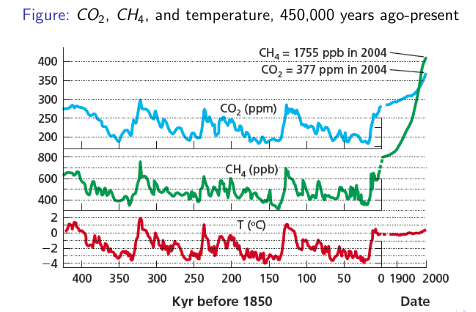

Looking at the Earth’s climate history, a rise in the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere was always associated to a rise in temperature:

GHGs emission and temperature fluctuations

The rise of GHGs concentration in the atmosphere has caused an increase in temperature from the start of the Industrial Revolution of about 0.9-1 ◦C:

Distribution of harm

Countries

- Adaptation capability, wealth, and technology may influence distributional consequences across countries.

- The primary reason that poor countries are so vulnerable is their location.

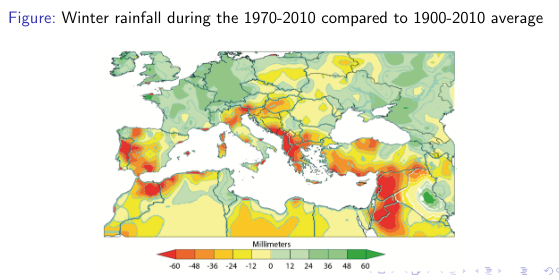

- Certain regions of the world are extraordinarily vulnerable to higher temperature, not only in poor and dry parts of the world (e.g. the Sahel), but also in other (richer) regions (e.g. the US Southwest, The Mediterranean basin, the eastern Mediterranean).

- The Mediterranean basin has experiences a significant trend of drying over the last century. If we continue with BAU, this region could experience further dramatic drying with quite devastating consequences to economies, nature, ecosystems and food security.

- The combination of warmer temperatures and more drying will lead to massive losses in food productivity in many parts of the world, especially in the tropics and subtropics.

Poorness

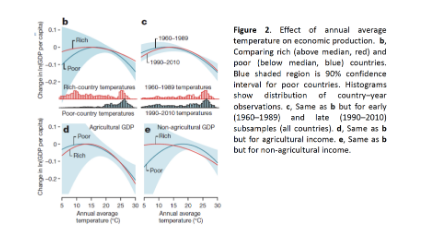

- Poor countries are more vulnerable to climate change than are richer countries as they are more exposed.

- Richer countries have a larger share of their economic activities in manufacturing and services, which are typically shielded (to a degree) against the vagaries of weather and hence climate change.

- Agriculture and water resources are far more important, relative to the size of the economy, in poorer countries.

- Poorer countries tend to be in hotter places

- Ecosystems are close to their biophysical upper limits, and there are no analogues for human behaviour and technology.

- The economic impacts of climate change

- Poorer countries tend to have a limited adaptive capacity as they lack the means, the wherewithal, and the political will to adapt.

- Limited availability of adaptation technology and ability to pay for those technologies.

- Limited human and social capital.

- They often do not have the capacity to prevent certain events before they manifest, and thus to be able to act on that knowledge.

- Political power is often controlled by a restricted elite, who may be aware of the dangers of climate change, but it may chose to ignore them if those impacts fall on the politically and economically marginalised.

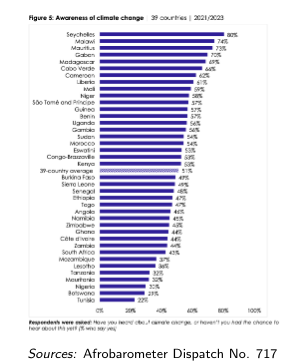

Climate change Awareness in Africa

Temperature and economic production

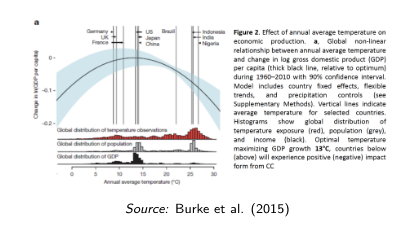

- Country-level economic production is smooth, non-linear, and concave in temperature, with a maximum at 13 °C.

- Both rich and poor countries exhibit similar non-linear responses to temperature.

- Technological advances or the accumulation of wealth and experience since 1960 have not fundamentally altered the relationship between productivity and temperature.

Effect on economic growth and development

Climate change will affect economic growth and development in four different ways.

Utility

- It may lead entire species to extinctions, and if their existence generate economic value (e.g. rare animals attract tourists), this leads to an economic loss.

Labour supply and Productivity

- Climate change may affect labour force through changes in mortality, or its productivity, and thus leading to a reduction of the output.

- For instance manual labour is harder in hot and humid climates.

- The increased demand for air conditioning can lead to increase productivity, but at the same time productions costs increase as well.

Positive impact in productivity?

- Tol (2019) considering 27 research papers show that initial warming has overall positive net economic effects, while further warming would lead to net damages.

- The initial benefits are due to reduced costs of heating in the winter, reduced cold-related morality and morbidity, and carbon dioxide fertilisations, which makes plants growing faster and more drought resistant.

- The incremental impacts turn negative before that, around 1.1 °C global warming.

- Probably we are already at that point, and considering the large inertia of the energy sector a warming of 2°C can probably not be avoided.

Capital depreciation

- Extreme weather events may lead to the disruption of infrastructures and thus leading to capital depreciation.

- More frequent floods for instance may wash away bridges, roads and buildings, and so there is less capital and thus less output and investments.

- More investments goes toward replacing capital and less toward expanding capital stock.

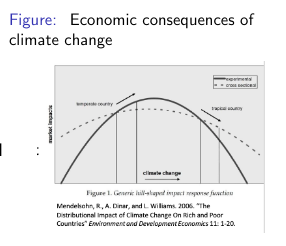

The impact in developing world - Mendelsohn et al. 2006

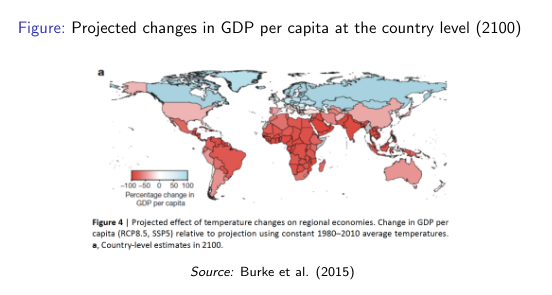

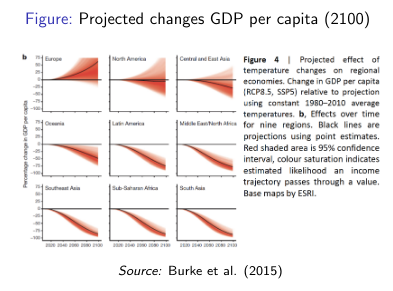

- The literature: the impact of climate change on rich and poor countries across the world.

- Developing countries were predicted to be slightly more vulnerable because so much of their economies were in climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture.

- Low technology operations are expected to have less substitution (Fankhauser, 1995; Tol, 1995).

- Assumed that almost every region would be damaged by warming.

- Climate-sensitive sectors have a hill-shaped relationship with absolute temperature.

- Countries in the low latitudes start with very high temperatures.

- Further warming pushes these countries further away from optimal temperatures for climate sensitive economic sectors.

- Latitude matters.

Poor countries will suffer the bulk of the damages from climate change

- Climate may contribute to trapping people in poverty.

- Some argue that climate and geography are contributing factors to (under)development, influential but no predominant.

- Climate change may increase infant mortality or the incidence of diseases (e.g. malaria or diarrhoea).

- Highly volatile environments may induce a feast-and-famine culture.

- Acemoglu argues that climate has been an important determinant in shaping institutions (education, rule of low, etc.).

How do we measure the impact of CC?

- Main focus has been on Agriculture Weather sensitive sector.

- Main economic sector in a developing country.

- Crucial for food security.

- Crucial for health and nutrition.

- Adequate diet for development.

Is all in agriculture?

New strand of literature looking at different impacts:

- Different economic sectors.

- Can you think at some examples?

- Different economic sectors.

- Conflicts, Migration.

- Human behaviour.

- Antisocial behaviour.

7

7

- Can you think at some examples?

Dell et al. 2012 Political instability

- Examine the effects of temperature and precipitation on a single aggregate measure: economic growth.

- Historical T and R data for each country and year in the world from 1950 to 2003 and combine this dataset with historical growth data.

- Temperature may also impact growth if increased temperature leads to political instability, which in turn impedes investment and productivity growth

- If warm weather causes riots, in some fraction of cases these riots could spill over into political change and instability.

- Also, economic shocks from climate might provoke dissatisfied citizens to seek institutional change.

- Poor economic performance and political instability are likely mutually reinforcing.

- Also migration, which causes conflict.

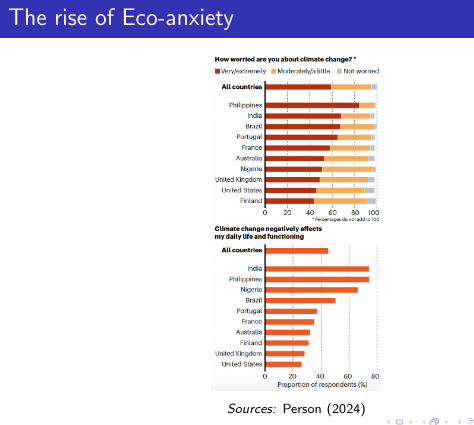

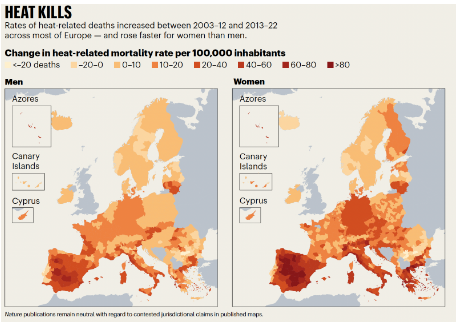

Europe

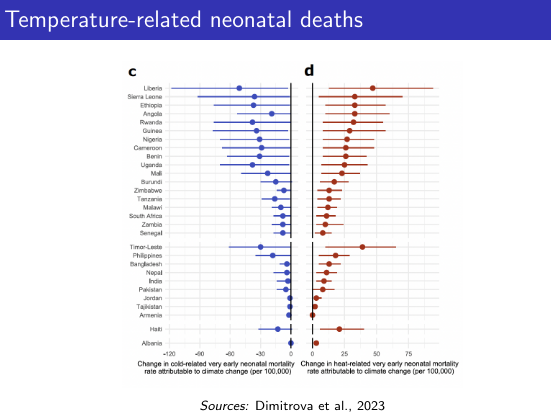

Neonatal deaths

Options for emission reductions

- Reduced population and economic growth would reduce emissions, but few elected governments would opt for this.

- Technological change reduces emissions but current effort would need to be trebled to stabilise emissions.

- Behavioural changes reduces emissions too, but habits are hard to change and market imperfections waste a lot of energy.

- Carbon-free fossil fuels are another option, but nuclear and hydropower are unpopular.

- Renewables are (very) expensive; volatile and unpredictable; and bring their own environmental problems.

Mitigation vs Adaptation

- There needs to be a strong global response to climate change, which can be reflected in two different ways.

- Mitigation, which means to reduce GHGs causing human-induced climate change.

- Adaptation, which means preparing to live more safely and effectively with the consequences of climate change.

- Adaptation reduces the need to mitigate climate change, and mitigation reduces the need to adapt.

Mitigation

- Mitigation requires some international cooperation, while adaptation does not.

- Effective mitigation depends on the actions of other countries.

- As the difficulties with reaching an international agreement on emissions became increasingly apparent, attention has shifted to adaptation.

Adaptation

- Adaptation includes any action to make the negative impact of climate change less bad, positive impact better, or even turn negative impacts in positive ones.

- Adaptation occurs on all levels of decision making, from individuals to the United Nations.

- Adaptation occurs on all time scale, it may be the response to past climate change or anticipation of future climate change.

- However, there are limits to how much we can adapt, because if the changes are so dramatic, then we are unlikely to be able to control the consequences of massive and worldwide crises.

- However, there are limits to how much we can adapt, because if the changes are so dramatic, then we are unlikely to be able to control the consequences of massive and worldwide crises.

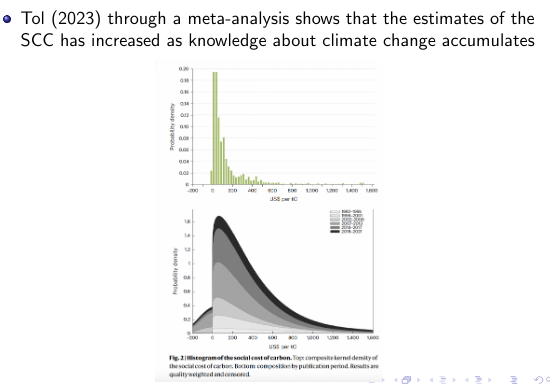

Pricing CO2 emissions: Social costs of carbon

- The most important single economic concept in the economics of climate change is the social cost of carbon (SCC).

- The SCC is a central concept for understanding and implementing climate change policies.

- SCC is an estimate of the economic damages/costs over the next 100 years that would result from emitting one additional tonne of carbon dioxide today.

- The social cost of carbon helps reveal how much society should sacrifice to avoid climate change.

- That’s because the social cost of carbon is the benefit – that is, the avoided damage – from reducing emissions of CO2.

- The SCC is estimated through Integrated Assessment Models (IAM).

- The social cost of carbon depends on many things:

- total economic impact of climate change.

- scenarios for population, economy, and emissions growth.

- the rate and level of global warming.

- the uncertainties about impacts and risk aversion.

- The discount rate.

- For an economy with no other distortions, the SCC equals the Pigou tax that internalises the externality and restores the economy to its Pareto optimum.

- Estimated as the Net Present Value (NPV) of the future climate change damages due to one additional metric ton of carbon dioxide.

- To convert future damages into present-day value a discount rate is applied that determines how much weight is placed on impacts that occur in the future. It is also called the time preference rate.

- Using higher discount rates implies that future costs and benefits are generally considered less significant than present costs and benefits.

Example

- The Obama administration introduced the first estimated social cost of carbon and it was $43 a ton.

- This would mean that if you avoided one ton of emissions of carbon dioxide, you’re saving $43 in damage that would have otherwise occurred.

- The Trump administration estimate was 5 a ton, and the Biden administration estimate is around $51 a ton.

- The discount rate under Obama was around 3%, which raised to 7–10% with Trump.

- Because a lot of damages from climate change occur in the distant future, the use of a higher discount rate makes a huge difference and lowers the estimated damage by putting less weight on the future.

- Basically Trump admin wants to maximise benefits now, doesn’t care about later.

Nordhaus

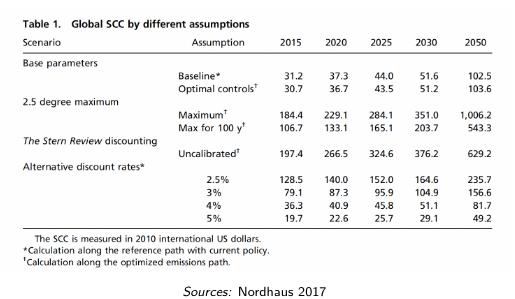

- Nordhaus (2017) provides an (updated) estimate of the global SCC of 37.3 US$ 2010/t CO2eq for 2020 (54.6 CHF 2010/CO2eq).

- This estimate was obtained based on potential damage to the global economy of 2.1% p.y. due to a 3 °C temperature increase (over 100 years) and the average discount rate of 4.25% p.y.*

- To constrain global warming to 2.5 °C (over the next 100 years), CO2 price should be set to 229.1 US$ 2010/t CO2eq for 2020 (Nordhaus, 2017), which corresponds with 335 CHF 2010/t CO2eq.*

- Constraining temperature increase to 2 °C would only be feasible if technologies were available that allow substantial negative emissions by around 2050.