Non-Renewables

What are they

How do societies manage nature’s assets — some renewable, like forests and fisheries, others exhaustible, like oil and minerals — so that their benefits can be sustained over time?

- Non-renewable resources: stock declines with use (oil, gas, minerals).

- Renewable resources: stocks can regenerate (forests, fish).

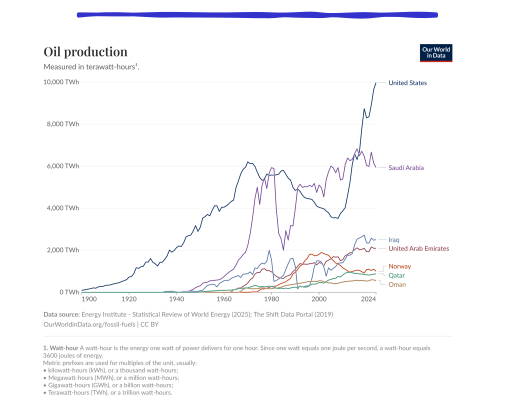

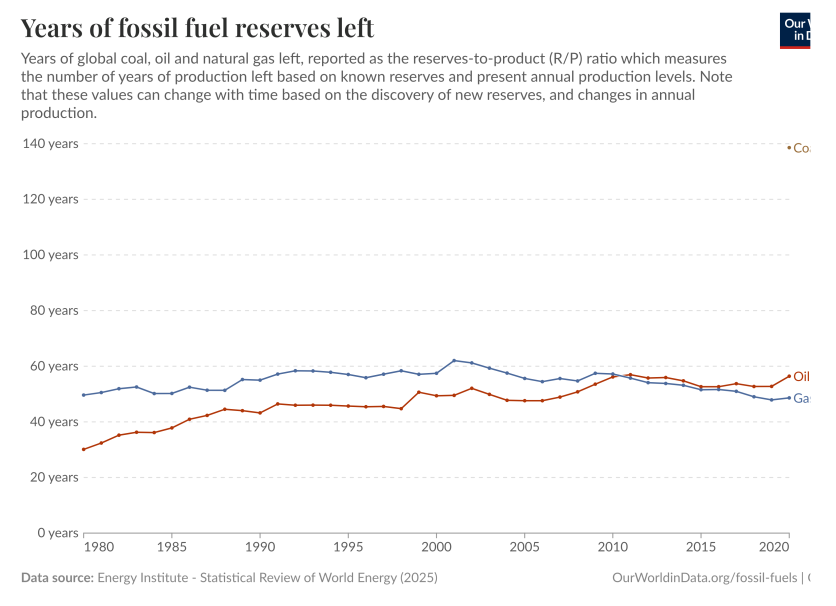

If oil is finite, why haven’t we run out yet?

A non-renewable resource is exhaustible — once extracted, it cannot regenerate within any meaningful human time scale:

A non-renewable resource is exhaustible — once extracted, it cannot regenerate within any meaningful human time scale:

- Extraction today permanently reduces the stock available for the future.

- A temporal trade-off: using a barrel of oil today means one less for tomorrow.

- The central question becomes how to allocate a finite stock optimally over time.

Oil production isn’t going down even though it’s exhaustible and the energy demand has gone significantly up. Should we expect an energy transition? When?

Effect on prices

Since we still have affordable prices something must be influencing it that’s not on this graph.

Since we still have affordable prices something must be influencing it that’s not on this graph.

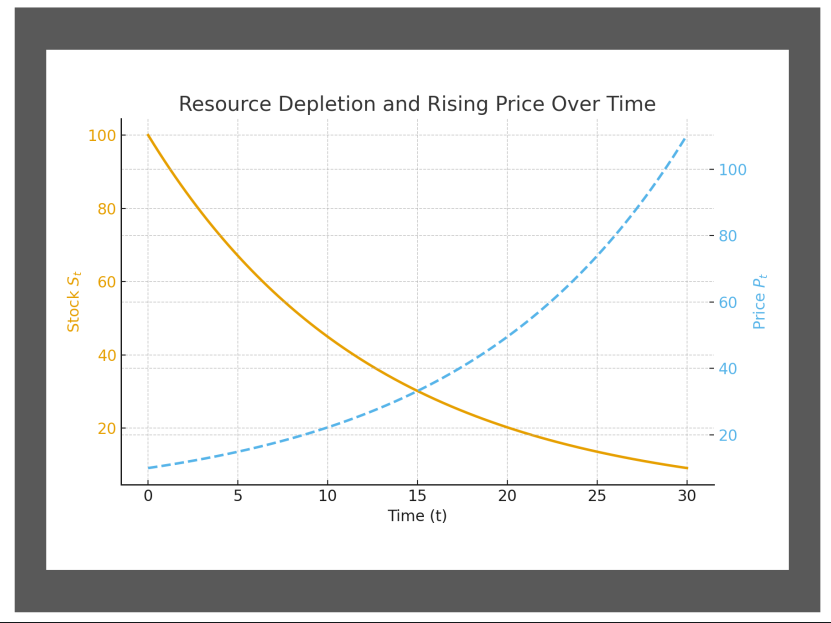

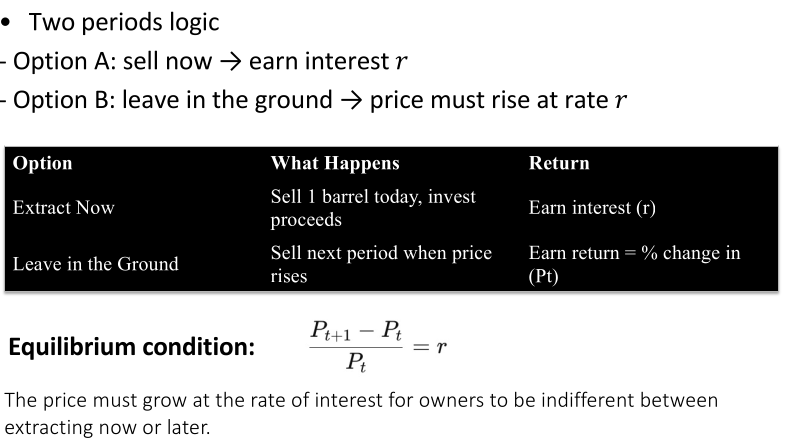

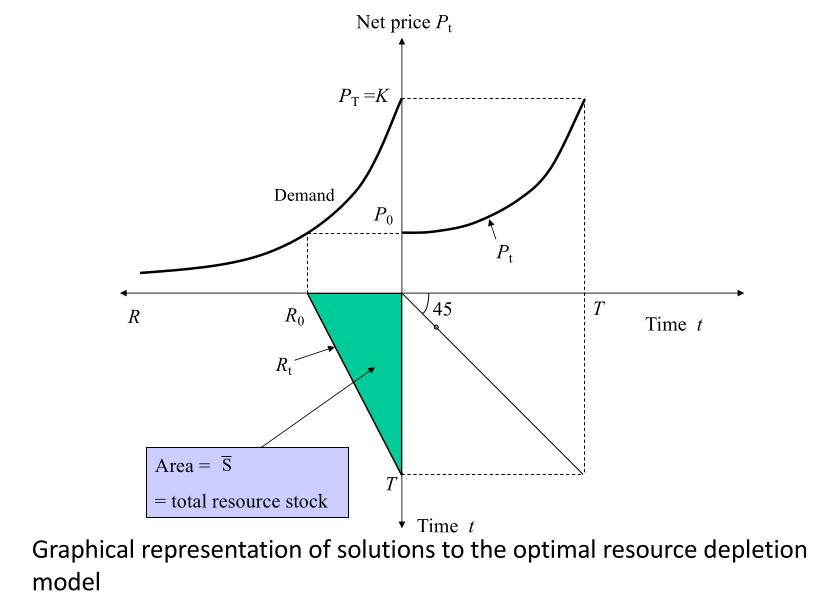

How should extraction evolve over time to maximise welfare?

Example 1

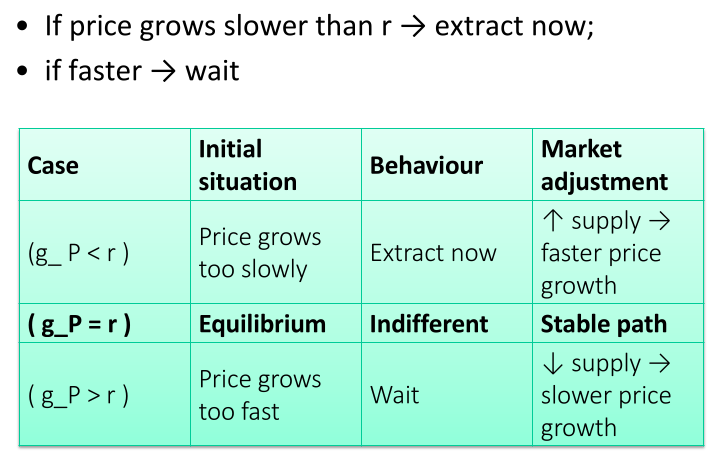

Expected return < r → Extract now

- P1=103→ expected price growth =3%.

- Expected return on the resource in the ground = 3%.

- Return on financial asset = 5%.

- The resource earns less in the ground than money earns in the bank.

- Decision: extract and sell now, invest proceeds. Interpretation: extraction is too attractive → the system over-extracts until price growth accelerates toward 5%.

Example 2

Expected return = r → Indifferent (equilibrium)

- P1=105 → expected price growth =5%

- Expected return on the resource in the ground = 5%

- Return on financial asset = 5%

- The owner is indifferent between extracting now or waiting.

- Decision: either extract or wait — both yield the same rate of return.

- Interpretation: this is the Hotelling equilibrium, where the discounted price is constant over time.

Example 3

Expected return > r → Wait

- P1=108 → expected price growth =8%

- Expected return on the resource in the ground = 8%

- Return on financial asset = 5%

- The resource in the ground appreciates faster than financial capital.

- Decision: wait and extract later.

- Owners delay extraction → current supply falls → current price rises, but with more stock left underground, future price growth slows until it equals the interest rate.

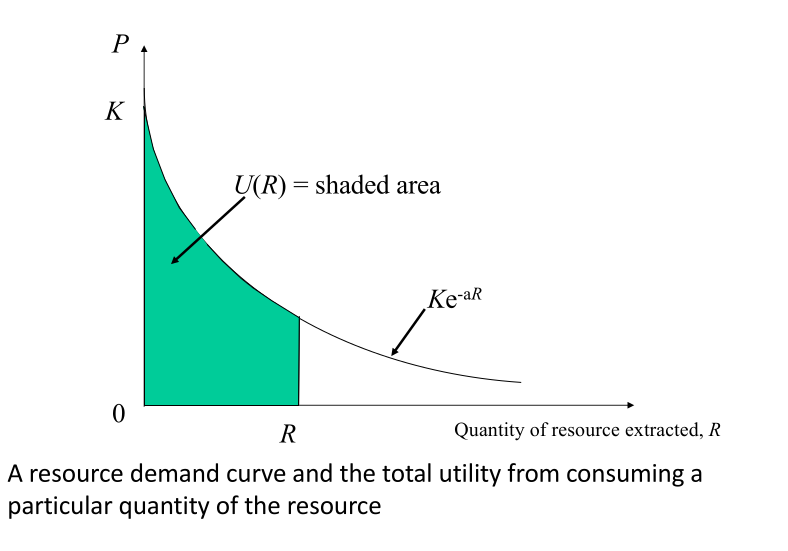

Demand

Extraction in perfectly competitive markets

- How will matters turn out if decisions are instead the outcome of profit-maximising decisions in a perfectly competitive market economy?

- Lots of companies or countries.

- Ceteris paribus, the outcomes will be identical.

- Hotelling’s rule and the optimality conditions are also obtained under a perfect competition assumption.

- It can be shown that all the results would once again be produced under perfect competition - provided the private market interest rate equals the social consumption discount rate.

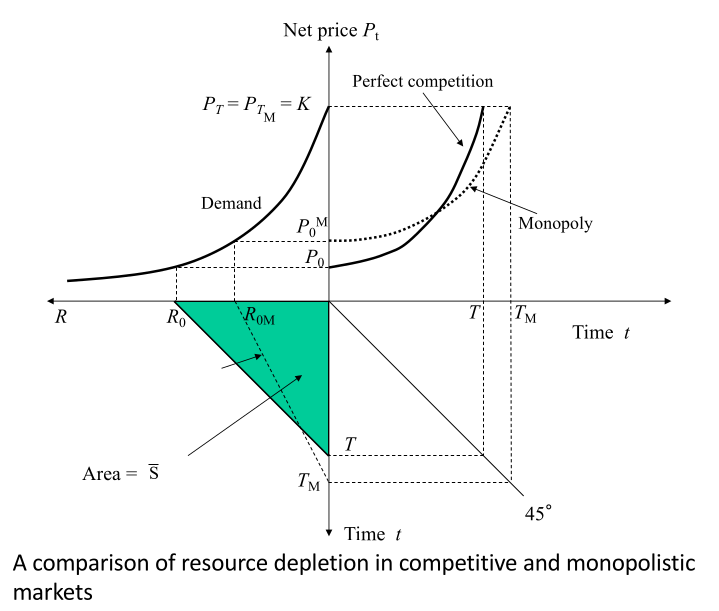

Extraction in a monopolistic market

- Monopolistic and competitive markets will differ.

- Under perfect competition, the market price is exogenous to (fixed for) each firm.

- Marginal revenue equals price.

- In a monopolistic market, price is not fixed, but will depend upon the firm’s output choice.

- Marginal revenue will be less than price in this case.

- The necessary condition for profit max in a monopolistic market states that the marginal profit (and not the net price or royalty) should increase at the rate of interest i in order to max the discounted profits over time.

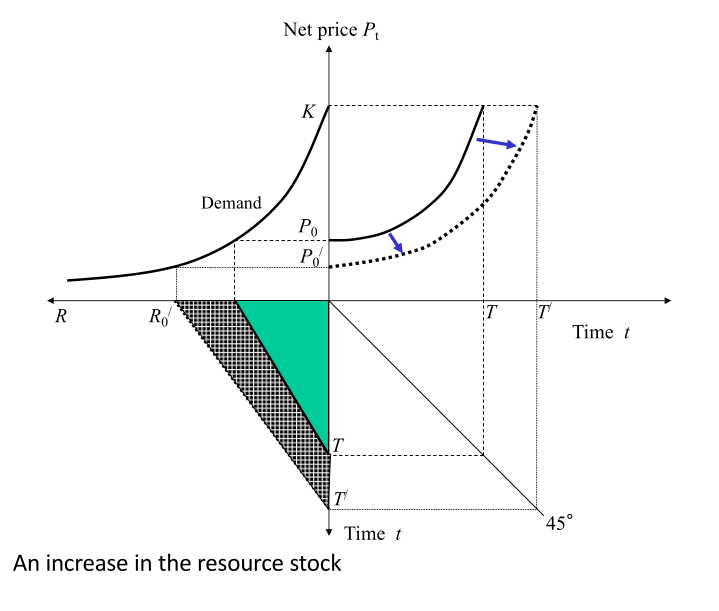

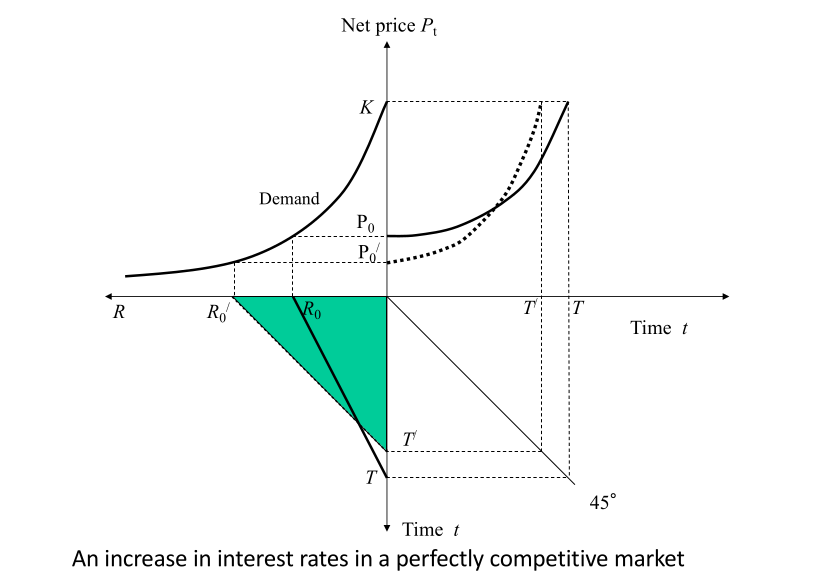

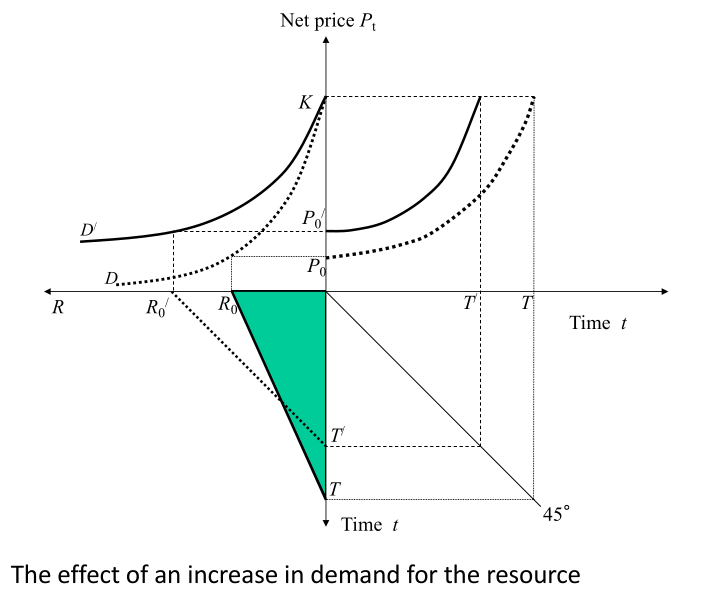

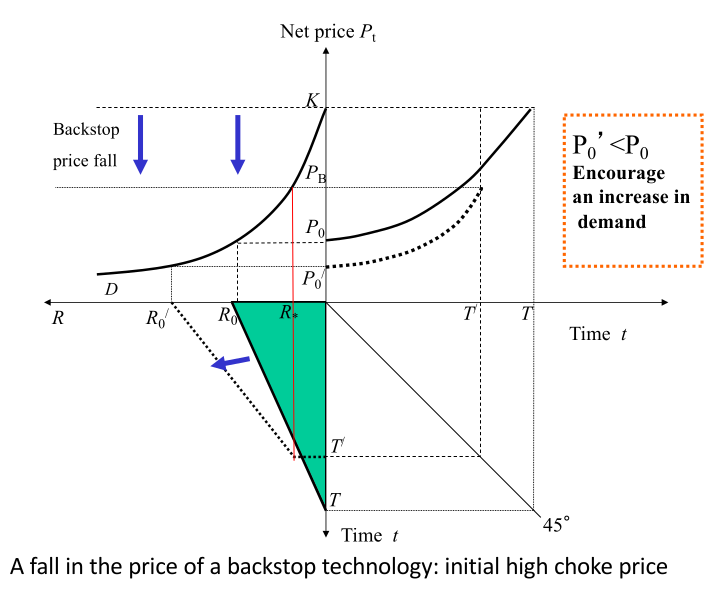

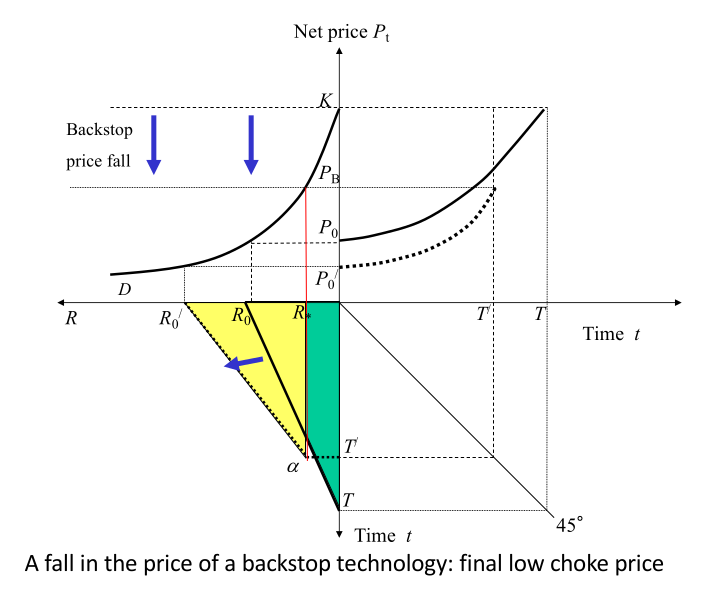

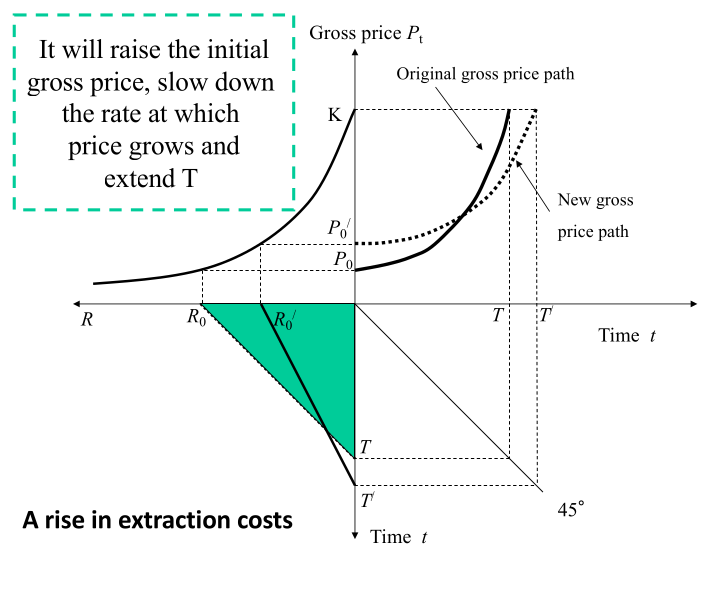

Comparative dynamic analysis

- Finding how the optimal paths of the variables of interest change over time in response to changes in the levels of one or more of the parameters in the model, or of finding how the optimal paths alter as our assumptions are changed.

- We adopt the device of investigating changes to one parameter, holding all others unchanged, comparing the new optimal paths with those derived above for our simple multi-period model.

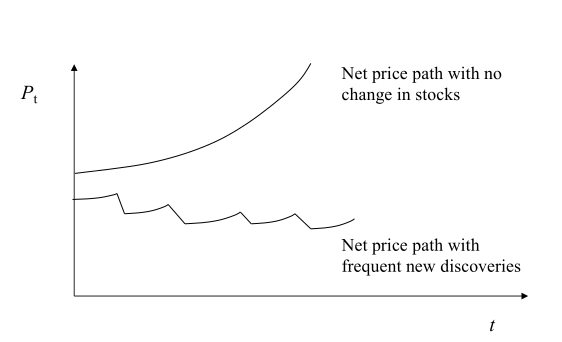

The effect of frequent new discoveries on the resource net price or royalty

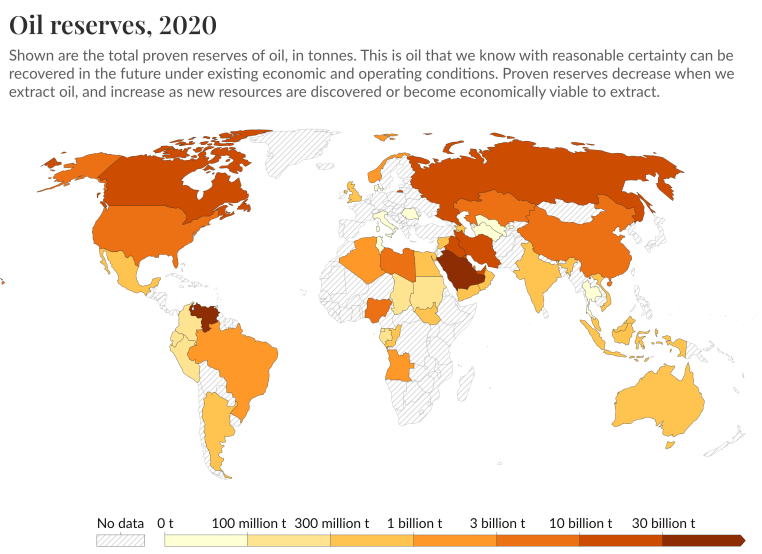

Estimates actually increased with time.

Estimates actually increased with time.

Effect of changes in interest rates, demand, backstop tech and extraction costs in prices

Why do firms invest in something they won’t be able to use? There is a strategical component, finding something before others do. Who knows when they might be able to use it, or if the other would…

Why do firms invest in something they won’t be able to use? There is a strategical component, finding something before others do. Who knows when they might be able to use it, or if the other would…

Hotelling rule and future energy model

- The dependence on non-renewable resources can be regarded as a huge problem (environmental or economic?).

- Once resources are used up energy consumption patterns will have to be adjusted at a great cost.

- On the other hand, the finiteness of fossil fuels can be regarded as a blessing.

- For as fossil fuel consumption must fall, carbon dioxide emissions must also eventually fall.

- Increasing scarcity must be reflected by raising prices.

Do resource prices actually follow the Hotelling rule?

Is the Hotelling principle sufficiently powerful to fit the facts of the real world?

- In an attempt to validate the Hotelling rule much research effort has been directed to empirical testing of that theory.

- No consensus of opinion has come from empirical analysis.

- Berck (1995) writes in one survey of results: the results from such testing are mixed.

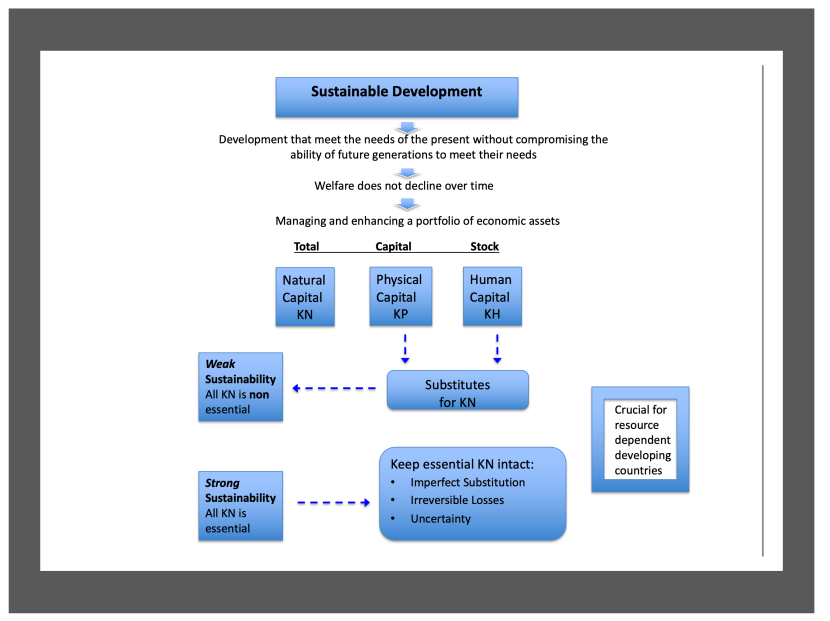

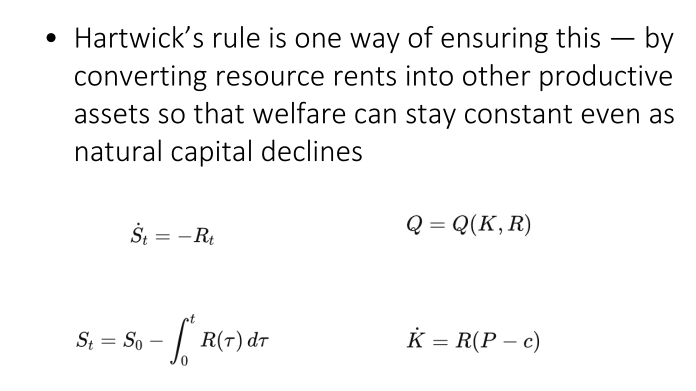

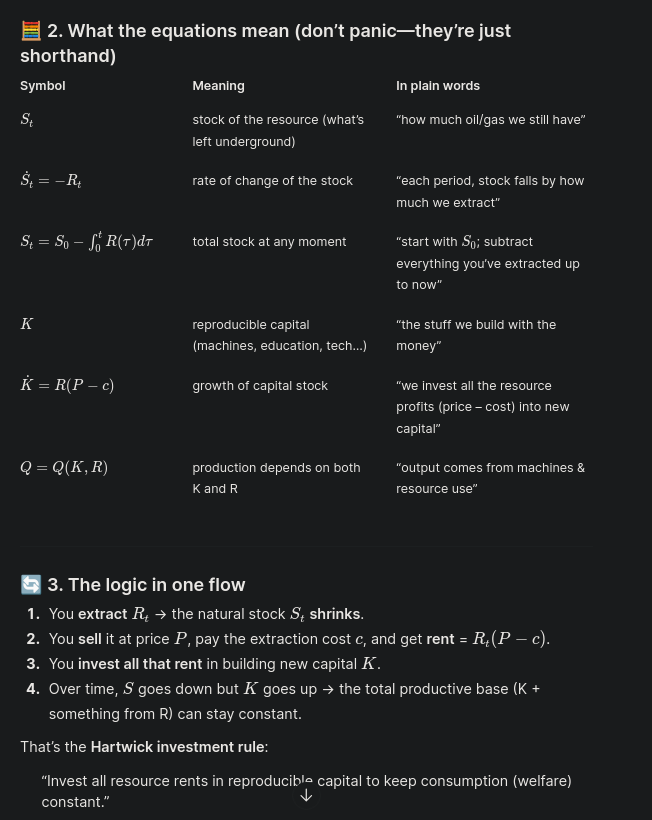

From Efficiency to Sustainability

- Hotelling’s rule → efficient extraction over time.

- But: efficiency doesn’t guarantee non-declining welfare.

- Solow (1986): We owe future generations not oil, but productive capacity.

- The challenge: as resource stocks decline, can total productive assets stay constant?

- Sustainability = maintaining total capital stock.

Takeaways

How to replace R’s contribution with K’s or viceversa though?

How to replace R’s contribution with K’s or viceversa though?